Key data for the fourth quarter show 2024 finishing on a healthy note, however, tariffs against Canada, Mexico, and China can potentially throw the economy off course. In 2024, GDP grew by 2.3%, with a favorable mix of final sales and inventories, and the Employment Cost Index showed a deceleration in wage inflation.

Although in the fourth quarter, GDP growth was below the 3% growth of the prior two quarters, the details indicate strong ongoing momentum in demand. Final sales of domestic products grew at a 3.2% rate, supported by a 4.2% jump in consumer spending. A slowdown in inventory accumulation subtracted 0.9% from GDP growth in the fourth quarter. The current rate of inventory accumulation is quite low relative to normal rates. The pattern of strong sales and low inventories in the fourth quarter bodes well for the first quarter.

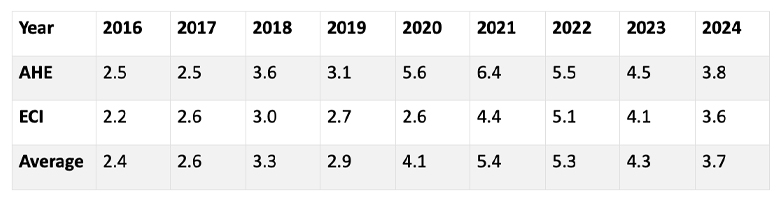

Another promising development was the ongoing slowing of labor cost inflation in the latter stages of 2024. The Employment Cost Index (ECI) for private sector workers rose 0.8% in the fourth quarter. On a year-over-year basis, it increased 3.6%, down from 4.1% in 2023. Moreover, the last two quarters of 2024 showed slower labor cost inflation than the first two. The average hourly earnings (AHE) data for production and nonsupervisory workers show similar patterns.

The table below summarizes the data for the ECI and AHE series. Those are two of the best measures of wage inflation. Although the data for 2024 show wage inflation is still modestly above the pre-COVID-19 levels of 2018 and 2019, the second half of 2024 data are actually quite close to the pre-COVID-19 levels. These labor costs data (if sustained over the next few months) should allow the Federal Reserve to resume easing sometime around mid-year.

Following its meeting on January 29, the Fed indicated it wanted to wait for more evidence of a decline in inflation before cutting rates again. The uncertainty about tariffs and their potential inflationary effects is one of the reasons for the Fed’s caution. On January 31, the White House announced tariffs of 25% on imports from Mexico and Canada and 10% on imports from China. While there may be exemptions or reduced tariffs for certain products (including energy imports from Canada) these tariffs will probably significantly affect inflation in 2025 and perhaps beyond.

In 2024, imports from Canada, Mexico, and China totaled approximately $480 billion, $560 billion and $470 billion, respectively. Together they account for 5% of GDP. The tariffs can broadly be viewed as a 20% tax on that 5% of GDP or about a 1% tax on the entire economy. Not all tariffs will be passed through to consumers through higher prices. Some foreign producers might choose to reduce their prices to maintain market share. Nonetheless, it appears likely that if these tariffs are sustained, consumer prices will be about 0.5% higher than they would be otherwise.

There are some second-order effects that both add and subtract from the first-order effects estimated above. The dollar has been appreciating in anticipation of tariffs (for example, it has been up about 6% against the Canadian dollar since June) and may continue to appreciate further. This will work to dampen inflation. On the other hand, American firms may raise prices in the face of reduced competition. Moreover, employees may seek and gain larger wage increases from their employers to compensate for the loss of purchasing power. The Fed will have to monitor these possible second-order effects carefully and may have to act to prevent inflationary expectations from rising. The tax hit of 1% of GDP will also work to slow down the economy, which will have its own implications for inflation. Retaliatory measures from Canada, Mexico, and China will likely have some effects on both growth and inflation.

The tariffs have also added to uncertainty, adversely affecting business psychology and investment. Their adverse effects on growth (especially if there are multiple additional rounds of retaliation) may be more significant than their effects on inflation.