In light of increasingly favorable economic data, it may seem strange to ask what could go wrong. As recent years—and history going much further back—have shown many things could go wrong. Pandemics, natural disasters, and wars occur regularly. But are there imbalances or risks specifically embedded in the economy or financial system that could contain the seeds of a reversal?

Within the U.S. economy, there appear to be three main risks. First are the relatively lofty valuations of the main assets held by households (stocks and homes) relative to historical averages. This has helped to support robust consumer spending but is a source of downside risk going forward. Second are wage inflation rates, still significantly above pre-COVID rates and inconsistent with the Federal Reserve’s 2% target for price inflation. Related to the second consideration is the possibility that the Federal Reserve will not cut rates as much as currently anticipated by the markets. Those are the main internal economic risks in the near term.

There are longer-term risks having to do with a fiscal situation that is probably unsustainable and, of course, political risks, especially in an election year. Internationally, there are some geopolitical risks familiar to any reader of the headlines, as well as a deflating real estate bubble that is causing China’s economy to slow down.

Several stock market indexes closed at record highs on multiple occasions in January. Stock market analysts are projecting earnings growth of over 10% in 2024, more than twice the likely growth rate of nominal GDP. Such optimism could set the stage for disappointment later this year.

Disappointment on earnings growth could be accompanied by disappointment about the speed and magnitude of interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve. During his press conference after the January 31 meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), Fed Chair Jerome Powell indicated that he wanted to see more evidence confirming the deceleration of inflation before cutting interest rates. His comments suggest that an easing of policy was unlikely at the next FOMC meeting on March 20. It now appears that the first rate cut will not come until the May 1 meeting or perhaps even later.

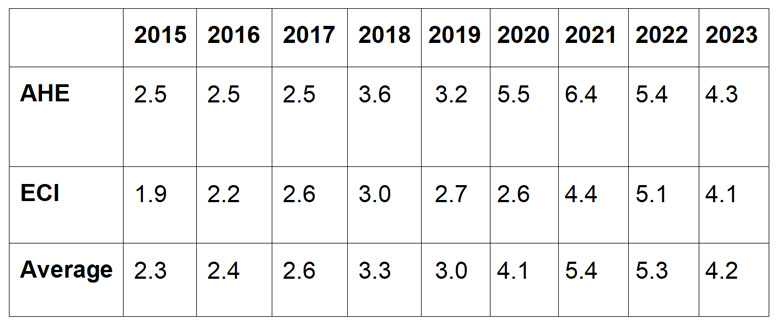

Powell’s caution is understandable. Although both price and wage inflation slowed substantially in 2023 it is unclear that inflation will return to the Fed’s 2% target anytime soon. The situation with respect to wage inflation can be seen in the table below.

The Employment Cost Index (ECI) for private sector workers and the average hourly earnings (AHE) for production and nonsupervisory workers are based on two different surveys. They sometimes diverge, but the broad trends (as the table below shows) are similar. Wage inflation accelerated significantly from 2019 to 2021. It has been slowing since. That is the good news. The somewhat concerning news is that it remains significantly above pre-COVID levels. If wage inflation stabilizes near current levels, it will be difficult for price inflation to move back to the Fed’s 2% target.

Under these circumstances, Powell and his colleagues are correct in wanting to see more evidence that inflation will continue to trend down. The most important such evidence would be an additional deceleration in labor costs during the first half of 2024.

The surge in equity prices that occurred during the last two months of 2023 and carried over into January appears to be partly based on some very optimistic and possibly inconsistent assumptions about earnings growth, inflation, and monetary policy. Of course, market optimism, or to use Alan Greenspan’s phrase from the 1990s, “irrational exuberance,” is nothing new. Moreover, it can continue for fairly long stretches of time. It is unlikely that the economy will fall off a cliff anytime soon. But it is worth noting that two of our recent recessions came as a result of the bursting of speculative bubbles—the bubble in technology stocks in the late 1990s and the bubble in house prices fed by the subprime mortgage boom in the following decade. Both were fed to a certain extent by easy monetary policy. Powell and his colleagues undoubtedly want to avoid contributing to a repetition of this pattern.

_________________________