The retired Colonel is the latest veteran to receive long-delayed recognition.

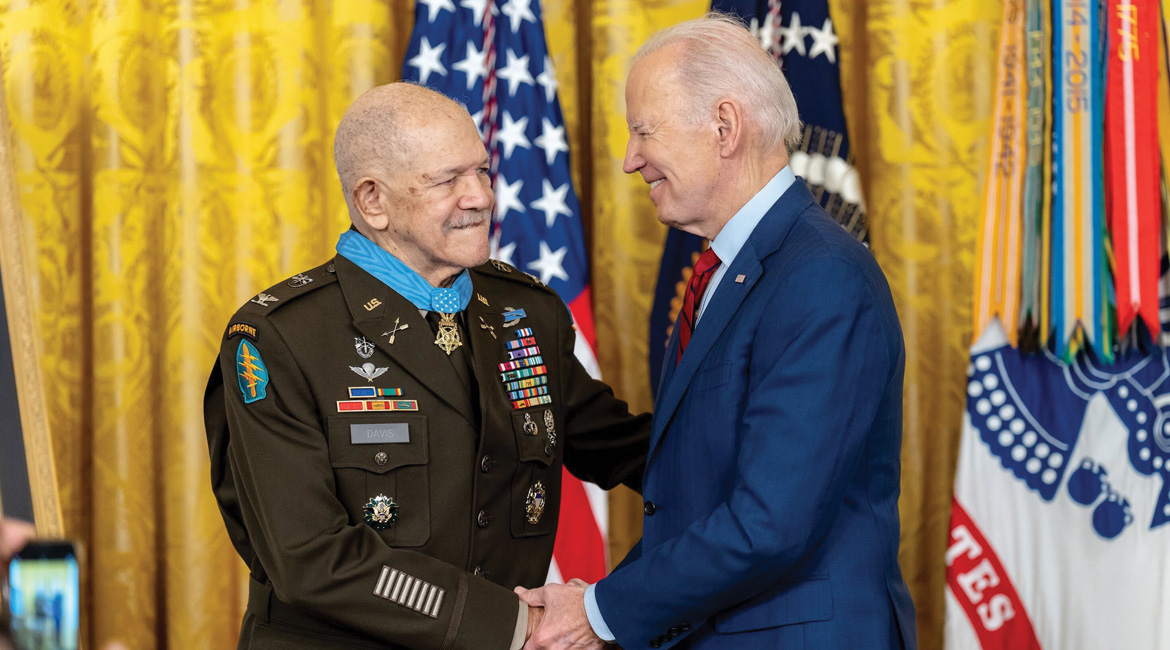

Above: President Joe Biden presents retired Army Col. Paris D. Davis with the Medal of Honor.

On March 3, 2023, President Joseph Biden presented the Medal of Honor to retired Colonel Paris Davis. It is difficult to comprehend why an 83-year-old man received our nation’s highest award for bravery in action. In this case, the action cited was not in a recent conflict but rather 60 years ago.

In doing a search of such presentations, the earliest we could uncover were some similar happenings during President William J. Clinton’s time in office. We learned that over two dozen medals had been awarded to men who were denied the Medal of Honor during World War II due to their race, ethnicity, or religion.

President Clinton made multiple presentations in 1997, bestowing the Medal to seven African Americans awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Three years later, President Clinton presented 22 Japanese American veterans with the Medal of Honor. They, too, had been denied the honor during the war. These men were members of the most widely decorated unit in World War II, the 442nd Regimental Combat. You may have seen their exploits in the movie “Go for Broke,” starring Van Johnson.

In 2014, President Barack Obama presented the Medal to the “Valor 24.” These individuals had been denied that honor based on their race or religion. Of those, seven were World War II veterans. The latest Medal awarded for action in World War II was to U.S. Army First Lieutenant Garlin Conner, whose Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal. His widow, Pauline Conner, accepted the Medal on his behalf from President Donald Trump in 2018.

Long Overdue Recognition

I watched the recent ceremony on CNN as President Biden presented the Medal to Col. Paris Davis. He was acknowledged as one of the first Black officers to lead a Special Forces team in combat. The ceremony was well attended as friends, family, and interested parties attended to witness the Colonel receiving his award. A humble and grateful Davis stressed the positive in his response by saying, “It is in the best interests of America that we do things like this.”

The long overdue recognition for this 83-year-old man came after the recommendation for his Medal was lost. It was then resubmitted and lost again. President Biden acknowledged someone in the audience and thanked him for all the efforts that made it possible for him to present the award on this day.

In an article in the WW II Museum, it is stated, “It wasn’t until 2016—half a century after Davis risked his life to save some of his men under fire—that advocates painstakingly recreated and resubmitted the paperwork.”

In presenting the Award, President Biden described Davis as a “true hero” for risking his life amid heavy enemy fire to haul injured soldiers under his command to safety. When a superior ordered him to safety, according to Biden, Davis replied, “Sir, I’m just not going to leave. I still have an American out there.” He went back into the firefight to retrieve an injured medic.

“You are everything this Medal means,” Biden told Davis. “You’re everything our nation is at our best: brave and big-hearted, determined and devoted, selfless, and steadfast.”

Davis should have received the honor years ago, and the delay in presenting the award was seriously questioned. “Somehow, the paperwork was never processed,” Biden said. “Not just once. But twice.”

It was reported that Davis’s commanding officer recommended him for the military’s top honor, but the paperwork disappeared. He eventually was awarded a Silver Star, the military’s third-highest combat medal. Still, members of Davis’s team have argued that his skin color was a factor in the disappearance of his Medal of Honor recommendation. “I believe that someone purposely lost the paperwork,” Ron Deis, a junior member of Davis’s team in Bong Son (Vietnam), told the AP in a separate interview.

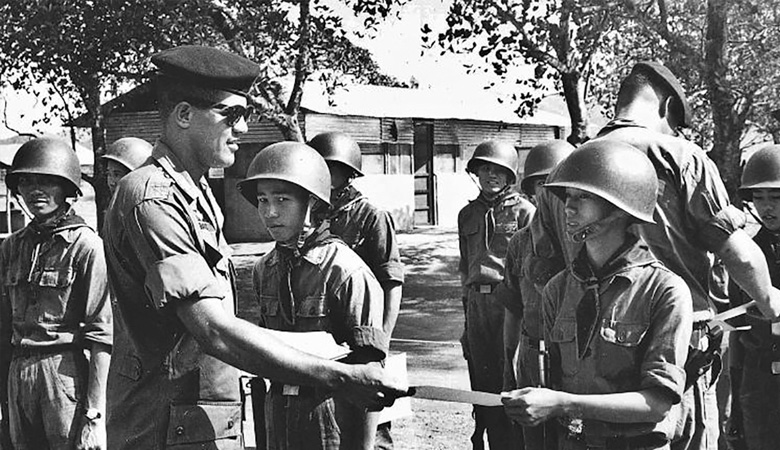

Capt. Paris Davis congratulates a soldier assigned to the 883rd Regional Forces for completing training, Vietnam, 1965. (Photo by Ron Deis)

Deis, now 79, helped compile the recommendation submitted in 2016. He said he knew Davis had been recommended for the Medal of Honor shortly after the battle in 1965, and he spent years wondering why it hadn’t been awarded. Nine years ago, he learned that a second nomination had been submitted “and was somehow, quote, lost.”

“But I don’t believe they were lost,” Deis said. “I believe they were intentionally discarded. They were discarded because he was Black, and that’s the only conclusion that I can come to.”

When asked in an Associated Press (AP) interview before the ceremony, Davis refused to dwell on the 60-year delay for him to receive this award. He responded that he did not know why decades had to pass before it finally arrived. “Right now, I’m overwhelmed.”

He added, “When you’re fighting, you’re not thinking about this moment. You’re just trying to get through that moment.” The details of the heroic and commemorative action were from the AP and stated by President Biden during the presentation ceremony.

Paris Davis’s Heroism

The award-winning action spanned nearly 19 hours and two days in mid-June 1965. Davis, then a captain and commander with the 5th Special Forces Group, engaged in nearly continuous combat during a pre-dawn raid on a North Vietnamese army camp in the village of Bong Son in Binh Dinh province.

The hard-fought battle entailed hand-to-hand combat with the North Vietnamese. Davis called for precision artillery fire and thwarted the capture of three American soldiers, all while suffering wounds from gunshots and grenade fragments. Davis used his pinkie finger to fire his rifle after an enemy grenade shattered his hand. Davis repeatedly sprinted into an open rice paddy to rescue his team members, according to the Army Times. Largely due to his efforts, the entire team survived.

“That word ‘gallantry’ is not much used these days,” Biden said. “But I can think of no better word to describe Paris.”

Davis, from Cleveland, retired in 1985 at the rank of colonel and now lives in Alexandria, Virginia, just outside Washington. Biden called him several weeks ago to deliver the news. Col. Paris Davis expressed at every opportunity that we should not dwell on the 60-year wait. “In no way [does that delay] lessen the honor,” he uttered.

The Army officials say there is no evidence of racism in Davis’s case. As someone who served in the Marine Corps from 1955–1959, I witnessed racism when we were onboard Navy ships. In my time, Pacific-based Marines spent a great deal of their time on LSTs (landing ship tanks), APAs (troop transport), and CVHs (helicopter assault carriers). The men who served us our meals were all Black, and their responsibilities consisted of kitchen duty. The same was true in our Marine Regimental Officers Mess (dining room) in our BOQ (bachelor officers’ quarters). The people who served us and maintained the facility were all Black. I must admit at that time, I did not believe what I was seeing was racist.

History Lesson

A WWII Museum article indicated that in early 2021, Christopher Miller, then the acting defense secretary, ordered an expedited review of the entire matter that Davis and his command experienced for those 19 hours and all that followed. He argued in an opinion column later that year that awarding Davis the Medal of Honor would address an injustice. That Col. Davis was awarded the Medal of Honor is an issue that rose above partisanship and that was clear in both the television presentation, as well as the AP and Museum articles.

History tells us that both Presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower were adamant that racism had no place in our military. It is fitting that a Democratic president, Truman, desegrated the military on July 26, 1948, when he signed Executive Order 998 1. President Eisenhower broadened Truman’s Executive Order by ordering the desegregation of military schools, hospitals, and bases. The last all-Black units in the United States military were abolished in September 1954.

Eisenhower became president in 1953 and did not want to support the desegregation order. He felt this way because he believed the Supreme Court should have made that decision. He did act because the Court decided not to hear the matter and corrected what he believed was left out of Truman’s Executive Order.

Sources

World War II Museum Article on Col. Paris Davis Black Vet Finally Awarded Medal of Honor March 3rd Associated Press Interview of Ron Deis a member of Davis’s unit in Vietnam. Wikipedia for dates and information regarding the desegregation of the military.

A Matter of Justice Eisenhower and the Beginning of the Civil Rights Revolution David A. Nichols – addressed Eisenhower’s changing position on desegregation in the military.

Harry & IKE The Partnership That Remade The Postwar World Steve Neal – the events leading to Truman’s decision to sign Executive Order 998 1.

To become a subscriber, visit https://thecannatareport.com/register or contact cjcannata@cannatareport.com directly. Bulk subscription rates are also available upon request and included in our media kit.