Much depends on what happens with the GDP.

The Commerce Department’s initial estimate for second-quarter GDP revealed a 0.9% decline. This followed a 1.6% drop in the first quarter. The decline in this year’s Q2 GDP mostly reflected a slower rate of inventory accumulation, which subtracted 2.0% from growth in the second quarter. Inventory accumulation has swung wildly in recent quarters, reflecting difficulties businesses have had in dealing with volatility in demand and supply chain issues. Inventory accumulation went from sharply negative as recently as the second quarter of last year (a decline of $174 billion) to unprecedented increases of over $230 billion in both the fourth quarter of last year and the first quarter of this year. The rate of accumulation dropped back to $118 billion in the second quarter, and the effect was to subtract 2.0% from GDP growth. During the second half of this year, inventories will probably continue to subtract from growth, but in a much more modest fashion.

As inventories normalize and stabilize, GDP growth should converge back to growth in demand. But even here, the picture has been one of weak or negative growth. Final sales to domestic purchasers declined by 0.3% in the second quarter, following relatively sluggish growth averaging 1.7% in the prior three quarters. Domestic demand was curtailed in the second quarter by declines in business investment in equipment and structures (down 2.7% and 11.7%, respectively) and residential investment (down 14.0%). Additional declines are likely in those sectors in the coming quarters.

Consumer spending grew by 1% in the second quarter, a slowdown from the average increase of 2.1% in the prior three quarters. This reflects a combination of losses of purchasing power from inflation, especially the rise in energy prices, and the waning effects of the fiscal stimulus enacted last year. We would emphasize, however, that households as a group are still sitting on massive gains in net worth that have accumulated in recent years. Moreover, gasoline prices fell sharply in July. It would not be surprising to see a re-acceleration in consumer spending in the second half of the year.

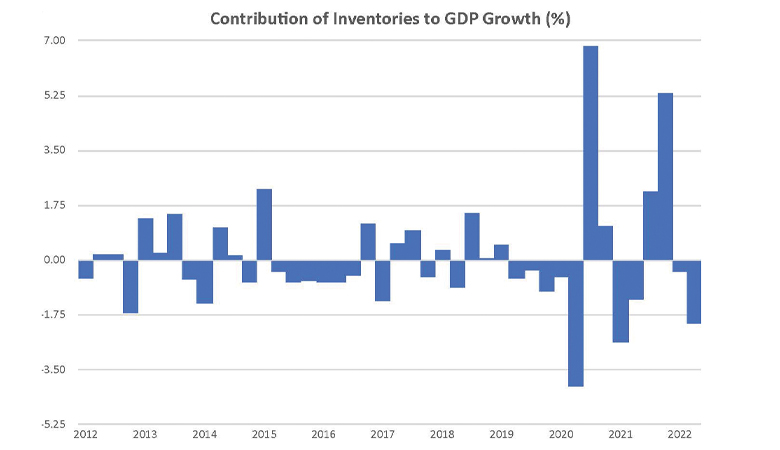

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses have had great difficulty managing inventories. Demand has become more unpredictable, and supply chain problems have often been severe and widespread. The effects of these challenges to inventory management on the economy are illustrated in the graph included here. Before COVID-19, there would be fluctuations in inventories, but in any given quarter, it was unusual that they would add or subtract more than 1% to GDP growth. Since 2020, we have seen quarters in which changes in inventories have added 6.8% to GDP growth (third quarter of 2020), 2.2% (third quarter of 2021), and 5.3% (fourth quarter of 2021), and quarters in which inventories have subtracted 4.0% from GDP growth (second quarter of 2020), 2.6% (first quarter of 2021), and 2.0% (second quarter of 2022).

Much attention has been focused on supply chain issues such as the shortage of chips that have affected automobile and office technology production. Inventory management has also been affected by how the pandemic has thrown a monkey wrench into previously predictable patterns of demand. First, there was a shift in spending away from services in favor of manufactured goods, then back toward services. Normal seasonal patterns of demand have been disrupted for certain products and the overall economy. It remains to be seen if demand stabilizes and returns to pre-pandemic patterns. Until then, many businesses will continue to experience challenges managing their inventories. And these challenges could remain sufficiently widespread to continue to affect the quarterly GDP data.

Even as growth slowed in the first half of the year, labor costs have accelerated. Each quarter the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes the Employment Cost Index (ECI). This covers benefits costs in addition to wages and salaries. The ECI for the private sector rose at an annualized rate of 5.8% in the first half of 2022. This is a sharp acceleration from 4.4% in 2021 and 2.6% in 2020. This acceleration indicates that the Federal Reserve is right to be concerned about a wage-price spiral, a situation in which inflationary pressure in the labor and consumer goods markets feed upon each other in a way that is difficult to stop. If this sort of dynamic takes hold, a mild recession might not be enough to break the upward spiral in inflation.

With these concerns as the backdrop the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised its main policy rate, the fed funds rate, by three quarters of a percentage point at its July 27 meeting. This followed a similar increase at its previous meeting in May. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and other Fed officials have continued to signal that more rate hikes are likely during the FOMC’s three remaining meetings this year.

Given the Fed’s rate hikes, the signs of an economic slowdown, and the high readings on the data for both consumer price inflation and labor costs, it was surprising to see the stock market turn in a very strong performance in July, with the S&P 500 rising by 9% over the course of the month. Even with the market downturn in the first half of this year, the financial condition of households remains strong. Over a three-year period, the S&P 500 is up 36%, and house prices have risen by 42%. Such gains in asset prices over a multiyear period will impart a certain resilience to consumer spending in the second half of the year. The declines in gasoline prices seen during July will also help to restore purchasing power lost in prior months.

At any given time, it is not unusual for the economic data to send mixed signals, with some data looking strong and others weak. The first half of this year brought slightly negative GDP growth in both the first and second quarters and very robust job growth, with non-farm payrolls increasing by an average $457,000 per month. When key economic data diverge like that, the truth is usually somewhere in between. I expect the two sets of data will show some convergence in the second half, with job growth slowing, perhaps sharply, and GDP growth returning to positive territory.

July also brought a disconnect between the stock market and adverse inflation news, and a Fed seemingly prepared to act aggressively to bring inflation down. Perhaps the market is assessing that inflation can come down on its own without the Fed having to do much more. A relief rally of sorts. This is probably wishful thinking. Both the wage and price data are consistent with inflationary pressures becoming more pervasive and deeply rooted. The Fed will likely have to tighten by more than the markets anticipate.

_________________________

To become a subscriber, visit www.thecannatareport.com/register or contact cjcannata@cannatareport.com directly. Bulk subscription rates are also available upon request and included in our media kit.