Look for an increase in the federal funds rate for the remainder of 2022.

The Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced a 0.50% increase in the federal funds rate on May 4, taking its target range to 0.75%–1.00%. This followed a 0.25% increase in March. Moreover, after the May 4 FOMC meeting in a press conference, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell indicated that additional 0.50% increases were likely at the next couple of meetings. The Federal Reserve also announced a plan to reduce its holdings of Treasuries and other securities.

Powell indicated that monetary policy was still too easy and the FOMC would be making some rapid adjustments to take policy to a neutral setting. He further indicated that neutrality would involve taking the target for the federal funds rate to about 3%. Given the current target range of 0.75%–1.00%, this implies an additional 2% increase in the federal funds rate over the course of the remainder of 2022.

The FOMC meets twice a quarter. Powell said that additional increases in the federal funds rate of 0.50% were likely at the next two meetings (June 15 and July 27). This would take the federal funds target range to 1.75%–2.00%. To get it up to 3%, additional increases would be needed in the last three FOMC meetings of the year. It is worth noting that even a 3% fed funds rate would represent a neutral policy. If inflation continues to be problematic, the FOMC could decide that policy needs to be tightened beyond a neutral setting. (Update: On June 15, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates by three-quarters of a percentage point.)

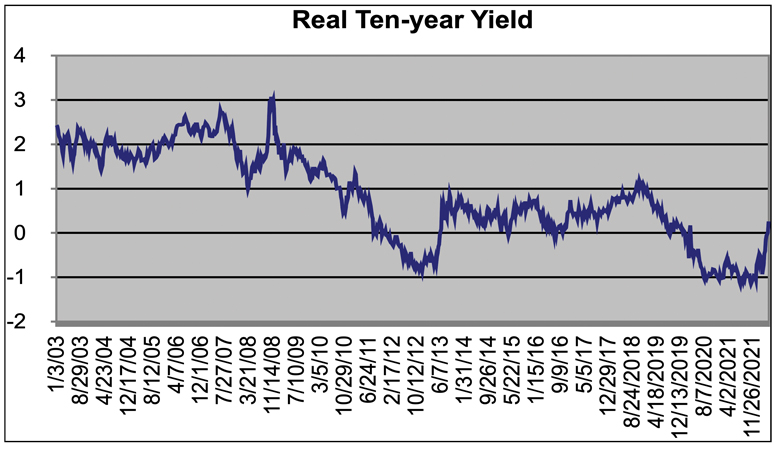

The bond and equity markets have taken note of the Fed’s words and actions. During the six-month period from early November to early May, 10-year Treasury yields have risen from 1.5% to over 3%. Mortgage rates have experienced a parallel increase. Real or inflation-adjusted 10-year Treasury yields (as determined from inflation-linked Treasuries) have risen more than 1% in the same period. In early May, they turned positive for the first time since March 2020. A slightly positive real yield tells us that monetary policy is not only as easy as it was in 2020 and 2021, but also that it remains quite accommodative.

The adjacent graph offers some perspective on real 10-year on inflation-linked Treasuries (using data from the Federal Reserve) over the past two decades. With the perspective of 20 years of data, even with the recent rise in rates, real yields remain unusually low. It shows that the Federal Reserve has only made a start in withdrawing the monetary stimulus provided during the pandemic. The normalization of monetary policy to neutral will likely involve real yields rising an additional 1% from current levels. A move to a “tight” monetary policy will entail an even larger rise in real yields.

The equity market has also reacted to the changing monetary environment. The S&P 500 finished the first week of May down 14% below its close for 2021. However, it was virtually unchanged from year-ago levels. Simply put, the equity market has unwound only a fraction of the massive appreciation seen in recent years. It remains very expensively valued relative to traditional fundamental metrics such as corporate profits. Moreover, the increases of prior years continue to provide strong support for consumer spending. Even with the decline so far this year, the S&P 500 is up over 70% in the past five years and more than 40% over the past three years.

Much the same could be said of house prices. The median price of existing homes sold has increased by almost 40% in the past three years. This too has created a powerful wealth effect that is boosting consumer spending.

In his post-meeting press conference in early May, Chairman Powell emphasized that increases in the federal funds rate in and of themselves would not bring about the rebalancing of the economy needed to tame inflation. Rather, he indicated that he and other Fed officials were keeping a keen eye on the financial variables that play a key role in transmitting monetary policy. These include equity and house prices, credit spreads, the yield curve, and foreign exchange rates. Powell emphasized that no single financial indicator dominates the Fed’s calculations. Rather, they look at the implications for the economy of all these financial variables collectively.

The reality, however, is that equity and house prices have, by far, the larger effects on the economy compared to other financial factors. Corrections in equity and house prices helped trigger recessions in 2001 and 2008. The Federal Reserve’s task over the next few years is to engineer a so-called “soft landing,” meaning to slow down the economy enough to bring down inflation without triggering inflation. This is never an easy task. It is complicated under current circumstances by the effects of the war in Ukraine on energy and other commodity prices, ongoing supply-chain disruptions, and uncertainty about how much more of an effect last year’s fiscal stimulus is still having on the economy.

What kind of guidelines might the Federal Reserve have in mind for some of these key financial conditions, especially the stock market? If there were no additional correction in equity prices, the economy would likely continue to overheat and a wage-price spiral (in which wage and price increases would feed upon each other in a vicious cycle) could develop. If there were an additional correction of over 30%, which would wipe out all the gains of the past three years, a recession would become likely. This suggests that the Federal Reserve would probably be most comfortable with an additional correction of 10%–20%. Of course, no Fed official would be that precise. They prefer to talk in general terms about overall financial conditions.

It is, of course, not possible for the Federal Reserve to precisely control asset prices. But the considerations discussed above suggest that it would consider changing the tone of its guidance once the market declines another 15% (which would take the S&P 500 to about 3,500). It would likely signal that it was done tightening policy if the S&P dropped below 3,000, effectively wiping out the gains of the past three years. A correction of that magnitude would put the economy in a situation like the correction after the tech bubble of the late 1990s, and would tilt the risks in favor of a recession and against a soft landing.

Access Related Content