The war in Ukraine has the potential to impact much more than energy prices.

Just like the equity markets, the economy, and the Federal Reserve were seemingly moving toward a period of normalization after the turmoil of COVID-19, but the Russian invasion of Ukraine has jolted everyone and introduced massive amounts of new uncertainty. The increase in uncertainty will surely have adverse effects on the U.S. and global economies, partly because businesses are likely to become more cautious about investment and hiring. This caution makes sense given the possibility of escalation—both with military and in the form of even more stringent sanctions and subsequent disruptions to trade and international finance.

Thus far, the main effects of the war in Ukraine and subsequent sanctions against Russia have been in the energy markets. The U.S. has banned imports of Russian oil. The U.K. has announced it would cease such purchases by December. Other countries that have imposed sanctions have a greater dependence on Russian oil and have not taken similar steps. Nevertheless, there have been significant disruptions in energy markets. This reflects uncertainties about dealing with Russian banks and other institutions that are being sanctioned. These uncertainties have had the effect of making buyers of oil and natural gas reluctant to deal with any Russian entities. Non-Russian businesses have also increasingly taken the stance that they do not want to be tainted by doing business with Russia. This is affecting willingness to trade with Russian businesses even for non-sanctioned products such as oil and natural gas.

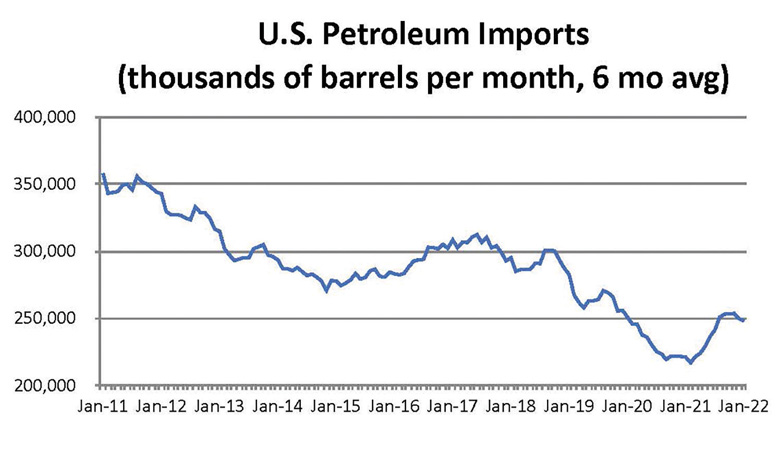

The effects of the invasion on energy prices in the days after the invasion were rapid and dramatic. This reflects Russia’s position as the world’s second largest oil exporter after Saudi Arabia. It is also a significant provider of natural gas to Western Europe. Although sanctions have carved out an exemption for purchases of oil and natural gas from Russia, this has not prevented a substantial rise in energy prices. Data from the U.S. Department of Energy show retail gasoline prices jumping 50 cents per gallon in the first week of March. Crude prices rose $25 per barrel during the same period. The U.S. is much better prepared to weather these price increases than during prior oil crises. The graph below (based on data from the U.S. Department of Commerce) shows how much U.S. imports of crude and refined petroleum products have declined in the past decade.

It should be noted that the decline in petroleum imports was especially sharp in 2020 when COVID-19 pushed the economy into a sharp contraction. Petroleum imports recovered last year but showed signs of returning to a downward path in recent months. The recent pattern on imports is mirrored by domestic production, which fell sharply in early 2020 but has been recovering. U.S. oil production dropped 19% from March 2020 to October 2020 but has since recovered half of this decline. The monthly pattern of oil production in the U.S. in 2021 was one with a clear upward trajectory. Data from the U.S. Department of Energy shows that production went from 343 million barrels in January to 351 million barrels in July to 358 million barrels in December. Even before the Russian invasion, drilling activity in the U.S. had picked up sharply. Data published by Baker Hughes reveals the count for oil rigs in early March reaching 650, a sharp increase from 403 a year ago. With the additional impetus from much higher prices, drilling activity is likely to accelerate further, and production should continue to show the strong upward momentum seen in 2021. It should be noted that drilling activity in Canada has also picked up sharply.

Looking at things from a longer-term perspective, U.S. oil production more than doubled from 2009 to 2019. This is the main reason for the decline in imports shown in the graph above. The reduced dependence on imported oil means that the U.S. economy will be much less adversely affected by a sharp rise in oil prices than in past decades. Among other NATO countries, the rise in oil prices will have a more substantial negative effect. Moreover, they are facing sharp increases in natural gas prices, though seasonal patterns will ameliorate demand for natural gas as warmer weather sets in. Unlike the oil market, which is globally traded, regional natural gas markets are often delinked from each other. This reflects limitations in the infrastructure to move natural gas from one market to another. Although oil and gas were exempted from the sanctions imposed against Russia, regional markets are being affected by the risk of interruptions in supply.

There are various ways through which the gap in the oil markets might be bridged. Diplomatic outreach has been made to various countries, including Venezuela and Iran, which might result in sanctions being lifted or eased in those countries. The current reluctance to deal with Russian counterparties with respect to energy purchases might ease. Russia might be able to sell more oil to countries that have not imposed sanctions. In turn, this will free up a certain amount of oil for those that have imposed sanctions. These considerations suggest that the spike in oil prices could ease in the months ahead.

However, the risks from the war in Ukraine are nearly unfathomable. The military conflict could escalate in various ways, including cyberwarfare or worse. Additional sanctions could be imposed. Countries not currently involved in the conflict might be drawn in. Russia and Ukraine are both major grain producers. Wheat prices have already risen over 50%, and there could be serious disruptions to grain supplies in the coming months.

In light of the above considerations, businesses will likely turn cautious when it comes to investing and hiring in the months ahead. Of course, the Russian economy will be much more severely affected. A depression-like contraction has already begun there, which could set off unrest or even refugee movements out of the country. In a short period of time in late February and early March, the world changed suddenly. The status quo ante is unlikely to be restored.

Access Related Content