A sudden surge in spending power could be right around the corner.

When Congress was debating the stimulus package enacted in December, there was little support for the idea of $2,000 stimulus checks being pushed by the unlikely alliance of Senators Bernie Sanders and Josh Hawley. All of that changed after the January 5th Georgia senatorial elections. The winning Democratic candidates had campaigned aggressively on this idea, and the Biden administration quickly made it part of its $1.9 trillion plan to turbocharge the economic recovery. The quick enactment of President Biden’s plan practically guarantees a strong surge in growth later this year, with some risk of supply bottlenecks and a transitory rise in inflation.

Of the $1.9 trillion authorized in the relief plan, about two-thirds will be spent in fiscal year 2021. The rest will be spent in fiscal year 2022 and beyond. However, even the $1.1 trillion being pumped into the economy this year is a massive sum of money, amounting to slightly more than 5% of the country’s Gross National Product. It includes stimulus payments of $1,400 per person for households making less than $150,000. Those payments were dispersed beginning in March and into April, putting approximately $400 billion in the pockets of American households.

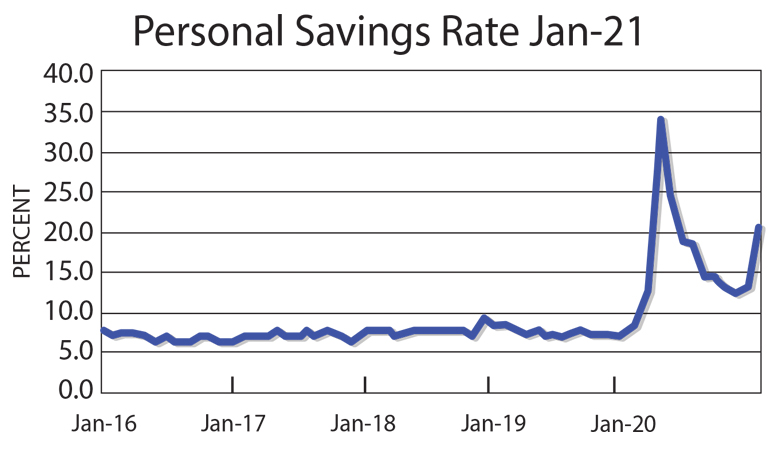

A key uncertainty is how quickly it will be spent. Data on the prior stimulus programs show a mixed picture, with lower-income households and those who have been hurt by the pandemic spending the money at a rapid clip. However, households that have been less adversely affected have saved a significant amount of the stimulus. The savings rate for all households combined rose from 7.5% in 2019 to 16.3% in 2020. The graph below shows the monthly data on the savings rate through January 2021, which is the most recent month for which the data have been published. The rise in the savings rate in January reflects the effects of the stimulus payments received that month.

Doreen, can you recreate this graph and fix Jan-21 where it looks like it is cut off?

In dollar terms, American households increased savings by $1.6 trillion in 2020, reflecting several factors. As alluded to earlier, one was the decision by many households not affected by the pandemic to save some of the stimulus funds. Part of that was undoubtedly a reflection of reduced opportunities to travel, eat out, go to movies, and other social activities. Another possible cause might have been an increase in precautionary savings. The pandemic and associated economic dislocations could well have made many households feel more insecure, including those not economically affected. It is a natural response to increase savings under such circumstances.

The question for 2021 and beyond is how much of this more conservative spending behavior gets reversed and how quickly. Rapid dissemination of vaccines will help to bring down the number of cases of sickness and deaths, hopefully, very sharply. Restrictions on economic activities will ease. Feelings of insecurity will also presumably recede. However, the timing of the adjustments in behavior is highly uncertain. The potential is there, however, for a large surge in spending in a compressed time period. Between the new stimulus checks ($400 billion) and last year’s increase in savings ($1.6 trillion), there is a potential $2 trillion in purchasing power.

With the number of cases and deaths from COVID-19 dropping and vaccination rates rising, the risk is growing that this $2 trillion dollars in purchasing power could produce a sudden surge in spending over the next two quarters rather than gradually over a longer period. Such a scenario could produce some significant supply bottlenecks and price increases. Already, production in the auto industry and other sectors has been curtailed by a chip shortage. Changes in international shipping patterns wrought by the pandemic have led to a scarcity of shipping containers in some ports.

The February survey of the manufacturing sector conducted by the Institute for Supply Management highlights the potential for widespread bottlenecks and other disruptions to supply chains if demand surges suddenly. Respondents to the survey noted depleted supply chains, major delivery issues, higher prices for inputs such as steel, a higher rate of delinquent shipments, and wide-scale shortages. These reports came from various industries, including computers and electronics, chemicals, transportation, food and beverages, appliances, plastics, and wood products.

The manufacturing sector is not the only sector where capacity will be tested. Many restaurants and other small businesses have been permanently shuttered because of the pandemic. As more people resume their normal activities, it will take time for new businesses to come online to meet the new demand.

Of course, one of the main rationales for an aggressive stimulus program is to bring the economy back to full employment as quickly as possible. The resulting side effects, such as supply bottlenecks, may be justified as worthwhile inconveniences for meeting more important economic policy objectives. Some of the side effects could also be dealt with down the road once the economy has regained a larger proportion of the jobs lost during the pandemic. As of February, employment was still down $9 million from pre-pandemic levels. The Biden administration has made the judgment it does not want to risk having too little stimulus, as was the case after the 2007–2008 economic crisis.

Financial markets have responded to the prospect of a turbocharged recovery by pushing up interest rates. The yield on ten-year U.S. Treasury bonds has risen from slightly less than 1.0% at the end of 2020 to over 1.5% by the second week of March. This reflects both expectations of faster growth and higher borrowing requirements by the federal government. The response to the pandemic has pushed federal debt held by the public to over 100% of GDP. It is not surprising that this is starting to produce an increase in interest rates.

The fiscal response to the pandemic in the United States is also quite large compared to other countries. It will, for a while, contribute to the widening of the trade deficit. Such a development will provide a bit of a safety valve for the bottlenecks and inflationary pressures that are likely to develop later this year.

Once the economy returns to something close to full employment, both fiscal and monetary policy will have to pivot from the extraordinary measures taken in the past year. This will be especially tricky given the Biden administration’s desire to pursue an ambitious infrastructure program. It has pledged to undo some of the tax cuts enacted in the previous administration for households making over $400,000. It remains to be seen if such measures will be enough to restore balance to fiscal policy.

Access Related Content

Visit the www.thecannatareport.com. To become a subscriber, visit www.thecannatareport.com/register or contact cjcannata@cannatareport.com directly. Bulk subscription rates are also available.